The Monarch Butterfly: A Marvel of Nature’s Design:The monarch butterfly, renowned for its striking appearance and remarkable migratory journey, stands as one of the most studied and iconic butterflies worldwide. With its vivid orange wings adorned with black veins and white spots, the monarch’s beauty is surpassed only by its extraordinary behavior. Millions of these butterflies embark on a seasonal migration, traveling from North America to the warmer climates of California and Mexico for the winter months.

Physical Characteristics and Identification

Easily recognized by its bold orange wings, the monarch butterfly is among the most conspicuous species in North America. Its wingspan ranges from three to four inches (7 to 10 centimeters), with two sets of wings that exhibit deep orange hues bordered by black and marked with white spots along the edges. The undersides of the wings are a soft orange, providing subtle contrast. Males can be distinguished from females by two black spots on the center of their hind wings, which are scent glands used to attract mates. Females, conversely, possess thicker wing veins. The body of the butterfly is black with distinct white markings.

The monarch caterpillar, in its earlier stages, is adorned with striking yellow, black, and white stripes, growing to about two inches (five centimeters) before undergoing metamorphosis. At both ends of its body, it bears tentacle-like appendages resembling antennae. The chrysalis, or pupal stage, is a delicate seafoam green, speckled with small yellow dots along its edges, a spectacle of nature’s subtlety.

Distribution and Habitat

Although the monarch butterfly is native to North and South America, it has spread to other regions with suitable climates and milkweed habitats. In North America, monarch populations are divided into two main groups: the western monarchs, which breed west of the Rocky Mountains and migrate to southern California for the winter, and the eastern monarchs, which breed in the Great Plains and Canada, migrating to central Mexico. Additionally, monarchs have been introduced to areas in Hawaii, Portugal, Spain, Australia, New Zealand, and various islands in Oceania.

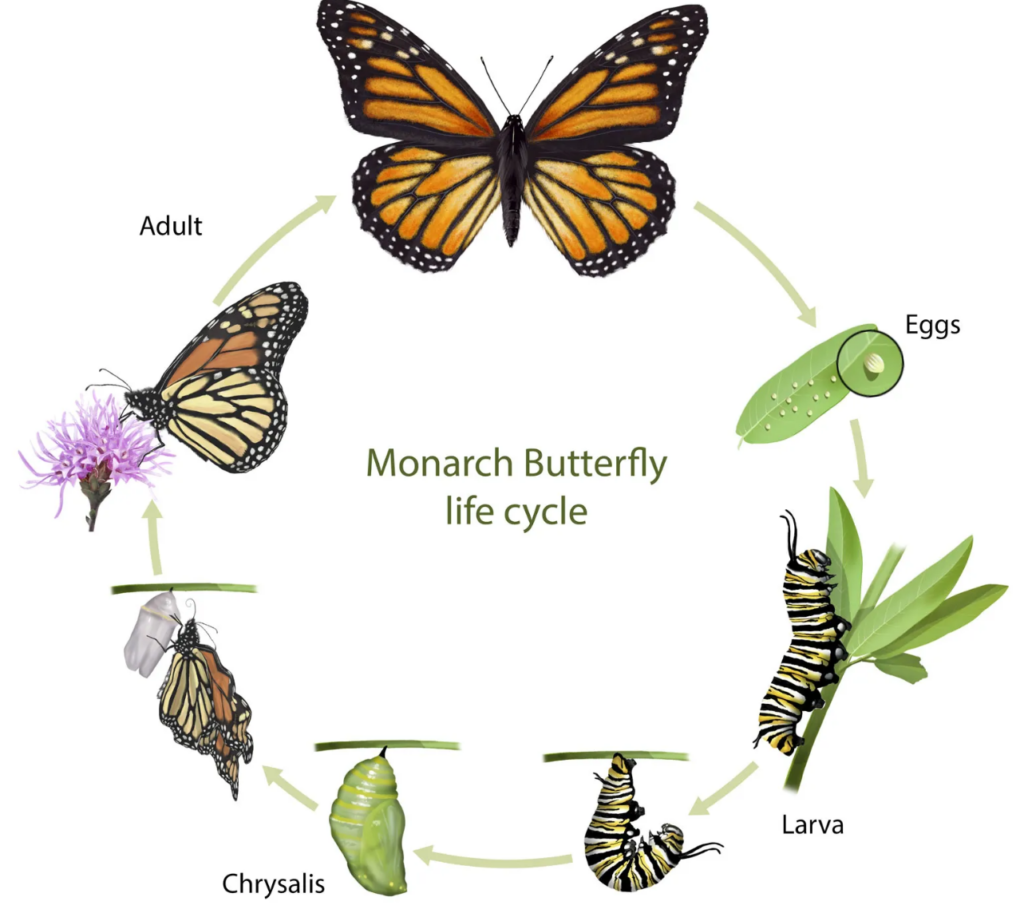

The Monarch’s Life Cycle

Female monarchs lay their eggs individually on milkweed leaves, using a secretion to attach them securely. Over a period of two to five weeks, a female may deposit between 300 and 500 eggs. After several days, the eggs hatch into larvae, commonly known as caterpillars. Their primary focus is nourishment, consuming only milkweed, the plant on which the female has chosen to lay her eggs.

The caterpillars grow rapidly, feeding for approximately two weeks before entering the pupa stage, where they form a protective chrysalis. Within one to two weeks, they undergo metamorphosis and emerge as adult butterflies, their black and orange wings fully formed. Monarch butterflies display different behaviors depending on their emergence. Those born in the spring or early summer begin reproducing shortly after their transformation, while those emerging in late summer or fall instinctively begin their long migration southward to escape the coming winter.

Defense Mechanisms

The vibrant coloration of the monarch serves as a warning to potential predators. The bold patterns signal that the butterfly is distasteful and poisonous. This toxicity is a direct result of their diet—milkweed, which contains toxic compounds. Monarchs have evolved to not only tolerate these toxins but also to store them in their bodies, making them unpalatable and dangerous to predators, such as birds.

The Remarkable Migration

Monarchs that emerge in late summer or early fall are the only ones to partake in the incredible journey southward for the winter. As daylight shortens and temperatures drop, they instinctively leave their breeding grounds in the northern United States and Canada, traveling to the mountainous regions of central Mexico, where they will wait out the cold months. Some monarchs travel up to 3,000 miles.

In Mexico, they cluster together on oyamel fir trees, forming large roosts to endure the winter. With the return of warmer temperatures and longer days, the monarchs begin their northward journey, laying eggs along the way. This process may repeat across four or five generations, eventually reaching the northern parts of North America.

Western monarchs, on the other hand, head to coastal California, where they overwinter at several known sites along the coast. In spring, they disperse throughout California and the western United States.

To navigate this immense journey, monarchs rely on the sun to guide them, but they also possess an innate magnetic compass that helps them find their way even on overcast days. A specialized gene for efficient muscle function further enhances their ability to undertake long-distance flight.

Conservation Concerns and Threats

Monarch butterflies face a multitude of threats, leading conservationists to call for their inclusion in the U.S. Endangered Species Act. While a decision on this matter is still pending, the decline in monarch populations is undeniable. Western monarchs have seen a staggering 99% decrease in numbers since the 1980s, while eastern populations have dwindled by an estimated 80%.

A primary factor in this decline is the loss of milkweed, the sole plant on which monarchs lay their eggs and the only food source for caterpillars. Milkweed, once abundant in agricultural fields, has been systematically removed due to the widespread use of herbicides and land management practices such as mowing along roads and ditches.

Climate change also poses significant risks to the monarch. These butterflies are highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations, and alterations in climate patterns may disrupt their biological processes, including reproduction and migration. Furthermore, extreme weather events—such as unseasonably hot or cold temperatures—threaten their survival and the availability of milkweed.

Conservation Efforts

Given their iconic status, monarch butterflies have garnered significant attention from conservationists, with numerous projects dedicated to their preservation across North America. Public campaigns encourage people to plant milkweed in their gardens, helping to restore habitats for monarchs. Citizen science initiatives also play a crucial role, enabling the public to assist researchers in collecting vital data that informs conservation policies.

Monarch sanctuaries, which protect the butterflies’ winter habitats, attract both tourists and funding that support ongoing conservation efforts. However, these sanctuaries are also vulnerable to the pressures of human development and conflict.

On a larger scale, efforts to protect monarch habitats, manage land more effectively for pollinators, replenish milkweed populations, and raise awareness are underway. These initiatives, coupled with ongoing scientific research, aim to ensure the survival of this magnificent species for future generations.

Diet

Monarch butterflies, like all other butterflies, experience a shift in diet during different stages of their life cycle. As larvae, monarchs feed exclusively on the leaves of milkweed, plants belonging to the genus Asclepias. North America is home to several dozen native milkweed species, with which monarchs have coevolved, and these plants are essential for completing their life cycle.

Milkweed produces toxic glycosides to discourage herbivores from consuming them. However, monarchs have developed immunity to these toxins. As the caterpillars feed, they accumulate these toxins in their bodies, making them unpalatable to predators. Remarkably, these toxins persist even after metamorphosis, continuing to protect adult monarchs from predation.

As adults, monarchs shift to feeding on nectar from a variety of native flowering plants, including milkweed.

Life History

Monarchs lay their eggs solely on milkweed, the only plant their caterpillars can feed on. The eggs hatch after three to five days, and upon emerging, the caterpillars consume their empty egg cases before beginning to feed on the milkweed leaves. Over the course of two weeks, the caterpillars grow and molt several times, eventually forming a chrysalis in which they undergo metamorphosis. Approximately two weeks later, they emerge as adult butterflies.

The lifespan of most adult monarchs is brief, lasting only a few weeks as they search for nectar, mates, and milkweed on which to lay their eggs. The final generation of the year, which emerges in late summer, delays sexual maturity and embarks on a remarkable fall migration—one of the few insect migrations of such scale. This migratory generation can live up to eight months.

The monarch’s annual life cycle and migration begin in their overwintering grounds in Mexico (for the eastern population) and coastal regions of central and southern California (for the western population). Around March, the overwintering monarchs begin their journey north. Once migration begins, the butterflies reach sexual maturity and mate. Females seek milkweed plants to lay their eggs, and after egg-laying, the adults perish, leaving their offspring to continue the migration. It typically takes three to five generations for the population to spread throughout the United States and southern Canada. The final generation of the year completes the journey southward to the overwintering grounds.

The monarch migration is one of nature’s most awe-inspiring phenomena. Monarchs instinctively know the direction to travel, despite never having made the journey before. They rely on an internal “compass” that guides them correctly each spring and fall, enabling them to travel hundreds or even thousands of miles.

Conservation

Since the 1990s, the monarch population has plummeted by approximately 90 percent. This decline is driven by habitat loss and fragmentation in both the United States and Mexico. For example, over 90 percent of the grassland ecosystems along the monarch’s central migratory flyway have been lost, converted into intensive agricultural lands or urban areas. Additionally, pesticides pose a significant threat: herbicides kill both the nectar plants on which adult monarchs feed and the milkweed that serves as the sole food source for their caterpillars, while insecticides directly kill monarchs. Climate change further complicates their survival, altering migration timing and weather patterns, which endangers monarchs during migration and while overwintering. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is currently reviewing the species’ conservation status.

One simple way to assist monarchs is by participating in the National Wildlife Federation’s Garden for Wildlife® program. This initiative encourages the creation of pesticide-free gardens filled with native milkweed and nectar plants. North America boasts several dozen species of native milkweed, with at least one species found in nearly every region. By using regional guides, you can select the best native nectar plants and milkweeds for monarchs in your area. These plants are chosen based on documented monarch visitation, their blooming periods coinciding with monarch presence, and their suitability for local growing conditions. You can also use the Native Plant Finder to discover additional native host plants for butterflies and moths in your zip code.

Planting native species is the most effective way to support monarchs, as their life cycles are intricately synchronized with the plants native to their environment. In recent years, tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica), a non-native plant, has become popular in garden settings due to its ornamental appeal and ease of cultivation. While monarchs readily lay eggs on tropical milkweed, its use in southern states and California has led to unintended consequences: it can encourage monarchs to forego migration and breed year-round, exposing them to the risk of disease and other complications. The National Wildlife Federation advises planting native milkweed and pruning tropical milkweed in the fall to encourage migration.

In addition to the Garden for Wildlife® program, the National Wildlife Federation’s Butterfly Heroes campaign involves families and children in raising awareness about the declining monarch population and taking action to help monarchs and other pollinators. Through the Mayors’ Monarch Pledge, cities across the U.S. are committing to creating monarch habitats and educating citizens on ways they can contribute to monarch conservation.

Roadsides also provide crucial habitat for migrating butterflies, and the National Wildlife Federation has partnered with other organizations to support the Monarch Highway initiative along Interstate I-35, which lies along the monarch’s central migratory route. The organization works with agricultural communities and lawmakers to protect and expand monarch habitat, as well as to restore the grassland ecosystems that monarchs depend on.

For more information on the National Wildlife Federation’s efforts to restore monarch habitats, visit their website.

The best way to assist monarchs, according to the National Wildlife Federation, is to restore their natural habitat by planting native milkweeds and nectar plants, eliminating pesticides, and encouraging others to adopt similar practices. Due to the risks of disease transmission, reduced genetic diversity, and bypassing natural selection, the National Wildlife Federation does not support the rearing of monarch caterpillars in captivity or the mass release of commercially farmed butterflies.

Fun Fact

Monarch butterflies communicate through scents and colors. Males attract females by releasing chemical signals from scent glands located on their hind wings. Monarchs also signal to potential predators that they are toxic by displaying their bright orange wings, serving as a warning that attacking them may come at a great risk.