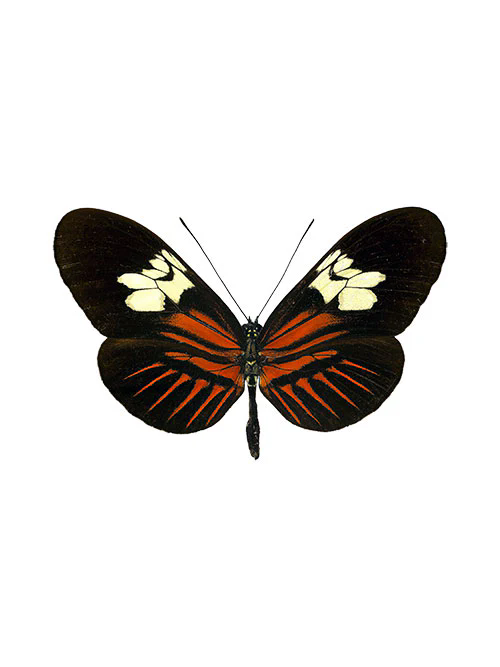

THE POSTMAN, HELICONIUS MELPOMENE

The Postman is a widespread species, occurring throughout Central and South America. In the wild, its wing colouration and markings vary depending on the location, with 30 different forms currently recognized.

The Postman looks almost identical to its comimic, the Small Postman (Heliconius erato). The best way to distinguish these two species is to look on the ventral side of the hindwing. The yellow line extends to meet the margin of the wing on the Small Postman (H. erato), whereas on the Postman (H. melpomene), the yellow line does not meet the margin of the wing.

Adults have an erratic flight and prefer sunny forest edges. They feed on both pollen and nectar. After mating, male Postman leave a scent on the females that deters other males. In Central America, females will only lay eggs on Passiflora oerstedii and P. menispermifolia, but in South America females will use any plant in the Passifloraceae family. Postman caterpillars are white with black hairs and spots with an orange head. They feed on passion vine (Passifloraceae). The chrsalids are light brown with gold spots and black spines.

Heliconius melpomene, the postman butterfly, common postman or simply postman, is a brightly coloured butterfly found throughout Central and South America. It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758.

The postman butterfly is predominately black with either red or yellow stripes across the forewings and has large long wings (35–39 mm).

Did you know?

The postman butterfly has a ‘daily round’, visiting the same sequence of flowers everyday.

Heliconius melpomene, the postman butterfly, common postman or simply postman, is a brightly colored, geographically variable butterfly species found throughout Central and South America. It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae. Its coloration coevolved with another member of the genus, H. erato as a warning to predators of its inedibility; this is an example of Müllerian mimicry.H. melpomene was one of the first butterfly species observed to forage for pollen, a behavior that is common in other insect groups but rare in butterflies. Because of the recent rapid evolutionary radiation of the genus Heliconius and overlapping of its habitat with other related species, H. melpomene has been the subject of extensive study on speciation and hybridization. These hybrids tend to have low fitness as they look different from the original species and no longer exhibit Müllerian mimicry.

Heliconius melpomene possesses ultraviolet vision which enhances its ability to distinguish subtle differences between markings on the wings of other butterflies.This allows the butterfly to avoid mating with other species that share the same geographic range.

Geographic range and habitat

Heliconius melpomene is found from Central America to South America, especially on the slopes of the Andes mountains. It most commonly inhabits open terrain and forest edges, although it can also be found near the edges of rivers and streams.It shares its range with other Heliconius species, and H. melpomene is usually less abundant than other species.

Origins

A recent study, using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) and mitochondrial DNA datasets, places the origin of H. melpomene to 2.1 million years ago.H. melpomene shows clustering of AFLPs by geography suggesting that the species originated in eastern South America.

Description

The postman butterfly is predominately black with either red or yellow bands across the forewings. The postman butterfly has large long wings (35–39 mm). It is poisonous, and the red patterns on its wings are an example of aposematism. They look similar to H. erato. Two features found on the underside of the hind wings help to distinguish H. erato from H. melpomene—H. erato usually has four red dots where the wing attaches to the thorax while H. melpomene usually has three. In Mexico, Central America and the west coast of Colombia and Ecuador, the yellowish-white stripe on the underside reaches the margin of the hindwing in H. erato but ends before reaching the margin in H. melpomene.

There are many geographical races/subspecies/morphs of this butterfly throughout Central and South America. The geographical variation in patterns has been studied using linkage mapping and it has been found that the patterns are associated with a small number of genetic loci called genomic “hotspots”. Hotspot loci for color patterning have been found homologous between co-mimics H. erato and H. melpomene, strengthening evidence for parallel evolution between the two species, across morph patterns.

Adults

Diet

Unlike most other butterflies, several Heliconius species have been observed eating pollen as well as nectar. The exact mechanism by which the butterfly digests the pollen is uncertain; it was originally thought that once the pollen was soaked in nectar after ingestion, it would then be able to be digested by the butterfly. Recently, however, the enzyme protease was discovered in the butterfly’s saliva, which implies an adaptation for breaking down pollen. This enzyme was found in higher concentrations in the saliva of female butterflies, likely due to the greater need of nutrition associated with reproduction. These adaptations allow the butterflies to extract important amino acids from the pollen, which, in addition to general nutrition benefits, allows H. melpomene to have brighter colors and be more distasteful to predators than their non-pollen-foraging counterparts. It is thought that this foraging adaptation and subsequent enhancement of coloration contributed to the speciation of Heliconius.

Pollination

Pollen is a rarely utilized but efficient protein source for Lepidoptera species. While foraging for pollen, adults accumulate pollen on the end of their proboscis and the grains stay there for long periods of time. These pollen grains are transferred to the stamen of another plant the butterfly visits while foraging. While there are many plants in H. melpomene’s range that provide suitable nutrients, only a few of these are visited by the butterfly. This makes the butterfly an efficient pollinator for the flowers it visits as there is a low likelihood of a plant receiving the wrong kind of pollen..

Life cycle

The eggs of H. melpomene are yellow and approximately 1.5 x 1 mm.They are mostly laid singly or rarely in small clusters on the young leaves of Passiflora plants. Caterpillars live in groups of two to three individuals and are white with black spots.Pupae are spiny and dark brown in color.The adults have black bodies with bright yellow or orange patterns on the wings. Female H. melpomene produce oocytes continuously throughout their life; this is due to the high nutrient diet the butterfly obtains from eating pollen.Closely related Heliconius species have been reported to have a maximum life span of six months, and it is likely that H. melpomene lives for a similar length of time.

Heliconius melpomene

Heliconius melpomene is a widespread neotropical species well known for its geographic diversity in colour pattern. Throughout its range, H. melpomene is co-mimetic with Heliconius erato, and both species have around 30 named geographic sub-species. H. melpomene is generally less abundant than H. erato, but both are found in open areas. H. melpomene can however be locally common in river edges and along streams.

H. melpomene is an ecological host plant specialist in Central America, where it only feeds on either Passiflora oerstedii or Passiflora menispermifolia. In other parts of the range however it is more of a generalist and can be found feeding on several different Passiflora species. Even in Central America, the larvae will happily develop on most species of Passiflora, so the specialisation is due to the oviposition preferences of the females (Smiley, 1978).

H. melpomene occurs from sea level to 1,400 m in forests edges. Usually individuals fly erratically and in the lower story. Females mate multiply and adults roost in small groups at night at 2-10 m above ground on twigs or tendrils.

The genetic basis of the geographic variation in colour pattern has been extensively worked out over many years of crossing experiments (Sheppard et al., 1985). Just a few genes of major effect control most of the changes. These loci have recently been shown to be shared across several different Heliconius species (Joron et al., 2006).