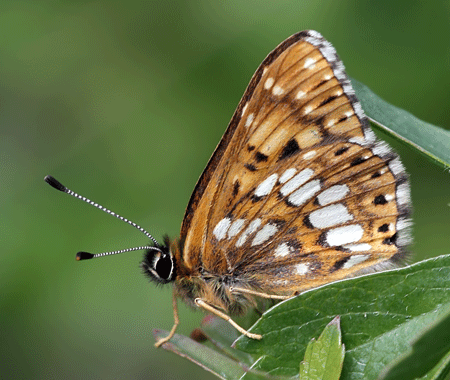

Wingspan: 29–34 mm. The Duke of Burgundy, the sole British representative of the subfamily Metalmarks, is a butterfly of particular intrigue. A distinctive feature of this family is that females possess six fully functional legs, while males have only four, with their forelegs significantly reduced. Although the sexes are similar in appearance, the male displays more black on its wings. This butterfly is primarily found in central and southern England. Historically, most colonies thrived in woodlands, where they bred on primroses growing in coppiced clearings. However, as coppicing has declined, most populations now inhabit scrubby downland, where cowslips serve as their primary food plant.

Life Cycle

The Duke of Burgundy produces one brood each year, with adults typically emerging in late April in southern regions, reaching their peak flight in mid-May. In some years, a partial second brood may emerge, although this is an exception rather than the norm, and typically occurs only in certain sites in southern England. The pupa serves as the overwintering stage.

Larval Food Plants

The primary larval food plants are cowslip (Primula veris) and primrose (Primula vulgaris), with false oxlip (Primula elatior) also occasionally used.

Nectar Sources

Adults feed on a variety of nectar sources, including tormentil, bugle, buttercups, hawthorns, and wood spurge.

Habitat

The Duke of Burgundy prefers warm, sheltered areas within limestone and chalk grassland scrub, or more open sections of ancient woodland.

Once primarily known as a woodland butterfly, the Duke of Burgundy once thrived on primroses in dappled sunlight, with colonies in both chalk and limestone grassland. However, the cessation of coppicing in woodlands has significantly impacted this species, leading to the extinction of many woodland colonies. In these woodlands, primrose was the primary larval food plant, while cowslip was more commonly found in grassland habitats.

This small butterfly is often encountered in scrubby grasslands and sunny woodland clearings, though it is typically seen in very low numbers. The adults are infrequent visitors to flowers; instead, most sightings consist of territorial males perched on prominent leaves at the edge of scrub. The females are elusive, spending much of their time either resting or flying low to the ground in search of suitable egg-laying sites. Scattered colonies can be found across southern England, though the species has experienced a significant decline in recent decades, particularly within woodlands.

As the only representative of the Metalmarks in the UK, the Duke of Burgundy’s closest relatives, particularly those in South America, are known for their metallic appearances. A distinctive feature of this family is the differing leg count between the sexes, with females having six fully functional legs and males only four, their forelegs being notably reduced. Initially classified as a fritillary due to its similarities to some British fritillary species, the Duke of Burgundy is now classified within the Metalmark family. Its range is confined to central and southern England, with scattered colonies also found in parts of northern England, such as Cumbria and Yorkshire. The species does not occur in Wales, Scotland, Ireland, the Isle of Man, or the Channel Islands. Though some colonies are relatively large, the majority consist of only a handful of individuals, with peak numbers rarely exceeding a dozen during the flight season.

Once categorized as a fritillary, the Duke of Burgundy’s striking markings have long drawn comparisons to these butterflies. However, it has now been reclassified within the Metalmark family. The butterfly’s population has suffered a dramatic decline throughout the UK, primarily due to habitat loss. The species has highly specific habitat requirements, and even seemingly suitable sites can become unsuitable as vegetation cover increases.